For Passover

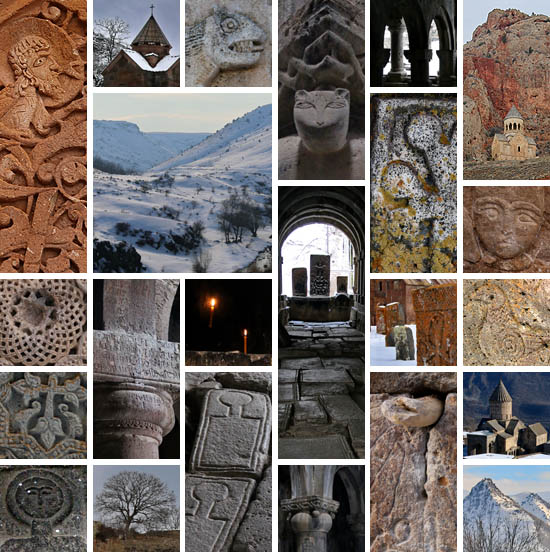

The Armenian Middle Ages in one hour

For a better overview, during our Armenian tours in May and June, of the maze of relationships during the period, and to see more clearly the importance of the individual monuments, next Wednesday, 27 April, I will give an one-hour lecture with maps and photos on the history of medieval Armenia, its regions and culture, with an emphasis on the regions that we will visit. The participants of our Georgian tour are also recommended to come, because, due to the intertwined history of the two countries, I will also speak about Georgia. Why did the Kurdish warlord found a Georgian church on Armenian land? Did any Hindu princes live in the village of the snakes, and do Frankish Crusaders still live in the valleys of the Caucasus? Which prince invited the Jews to the kingdom of Karabagh? How did the son of a Georgian rebel, converted to Muslim faith, become the father of an Armenian bishop? Why did the Prince of Syunik go on pilgrimage to the mother of the Mongolian Great Khan in Karakorum? Why did they keep the books in wine barrels at the theology of Haghpat? Where did the French ambassador first drink coffee, and how did he like it? These and other tantalizing questions will be answered by us on 27 April at 7 p.m. in our usual place, in the separate room of Selfie Restaurant (Budapest, Rákóczi Street 29, Google Map here). I will be there from 6 p.m. on, and will be happy to answer questions about the tours. It is also recommended that you arrive early, because serving such a large gathering goes slowly, and you are advised to secure your beer and salad in time.

Sayat Nova, the great 18th-century composer: Amen sazi mejn govats. Sayat-Nova Ensemble, Tovmas Poghosyan (2007)

magyarul

Eternal friendship

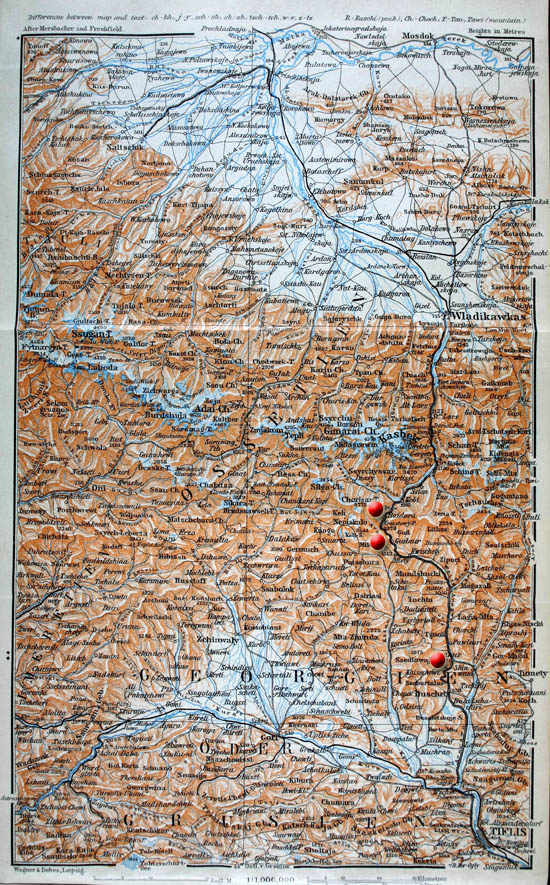

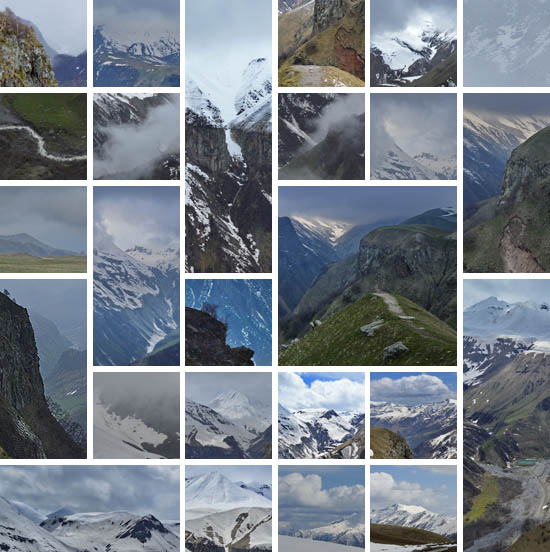

In the context of these celebrations there was inaugurated, a few hundred meters below the Holy Cross Pass, where one has the first beautiful sight over the southern slopes of the Caucasus when coming from Russia, or the last one when leaving Georgia, the Russian-Georgian Friendship Look-out, or as it is called in the Russian sites, Арка Дружбы, the Arch of Friendship, designed by Zurab Tsereteli. The look-out indeed offers a stunning panorama on the uppermost section of the Aragvi river in depth, called the Devil’s Valley in Russian, and of the huge clouds in the heights, drifting downward from the northern side of the Caucasus. No wonder then that everyone pulls off the military road to take a photo. Here I first heard some teenage girls use the Russian phrase давай поселфимся, “let’s make a selfie!”

In the context of these celebrations there was inaugurated, a few hundred meters below the Holy Cross Pass, where one has the first beautiful sight over the southern slopes of the Caucasus when coming from Russia, or the last one when leaving Georgia, the Russian-Georgian Friendship Look-out, or as it is called in the Russian sites, Арка Дружбы, the Arch of Friendship, designed by Zurab Tsereteli. The look-out indeed offers a stunning panorama on the uppermost section of the Aragvi river in depth, called the Devil’s Valley in Russian, and of the huge clouds in the heights, drifting downward from the northern side of the Caucasus. No wonder then that everyone pulls off the military road to take a photo. Here I first heard some teenage girls use the Russian phrase давай поселфимся, “let’s make a selfie!”

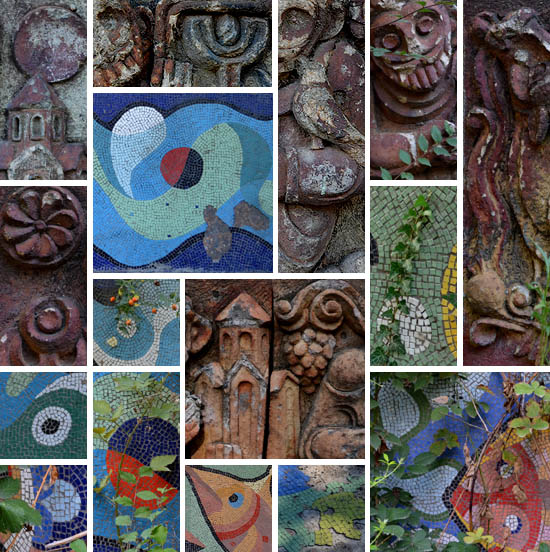

Reading of the mosaic decoration of the look-out starts from the center. A mother is sitting here with her child, surrounded by two groups of dragon-slaying knights, three Georgians and three Russians, as secular Holy Georges. This remote Madonna theme is likely the popular socialist allegory of “the next generation”. Next to her, the quote of Rustaveli in two languages asserts that a friend always helps his friend, and this is what we see unfolding in the panneau, basically from right to left, from the Russian side to the Georgian one. Already in the Middle Ages, Russians tolled church bells and rushed to the help the Georgians. (The artists here probably do not allude to the first chapter of Georgian-Russian relations, when Prince Yuri Bogolyubsky twice invaded Georgia in alliance with Muslims. Queen Tamar both times defeated him, and forgave him, and only after the third time was he sentenced to prison for life.) After the fairy tale figures come other heroes, the red sailor of the Revolution and the soldiers of the Civil War, the Soviet hero trampling on the swastika, and finally the image of the brave new world. On the Georgian side, the bucolic-ethnographic representation of Georgian folk life are likewise traced out, in a great leap, with revolutionary figures of the popular uprisings, and then the same brave new world. Life is day by day more joyful. As if even the shape of the building illustrated that verse of the national anthem: дружбы народов надежный оплот, “a strong bastion is the friendship of peoples!”

Союз нерушимый республик свободных – Unbreakable Union of Freeborn Republics

In the occasion of the celebrations, a friendship monument was erected not only at the middle of the route, but also at its two ends. Both were entrusted to the same Zurab Tsereteli, who, with genial pliancy, has since served all systems with his over-dimensioned monuments. The statue Узы дружбы, “The bond of friendship” at the start of the military road in Tbilisi, where the text of the Treaty of Georgievsk was written in the inner side of two interlocking rings, was demolished in 1991, and I failed to find a photo of it.

In Moscow, however, still stands the column called Дружбы навеки, “Eternal friendship”, crowned with Russian ears of corn, embraced by Georgian vine, and announcing in two languages the words “Friendship”, “Union”, “Work” and “Peace”. The column was erected in the center of the former Gruzinskaya sloboda, the former estate of the Georgian king Vakhtang VI. For a long time, this square hosted the Georgian market, whose removal provided the Moscow city government with the necessary space to raise the column of Russian-Georgian friendship.

In Moscow, however, still stands the column called Дружбы навеки, “Eternal friendship”, crowned with Russian ears of corn, embraced by Georgian vine, and announcing in two languages the words “Friendship”, “Union”, “Work” and “Peace”. The column was erected in the center of the former Gruzinskaya sloboda, the former estate of the Georgian king Vakhtang VI. For a long time, this square hosted the Georgian market, whose removal provided the Moscow city government with the necessary space to raise the column of Russian-Georgian friendship.

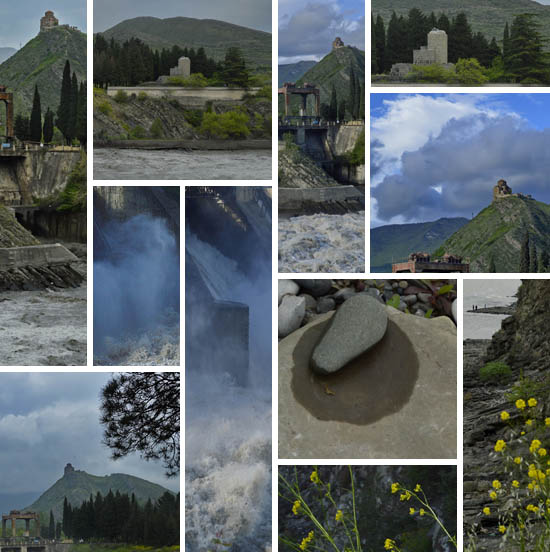

Two years later, in 1985, another monument was inaugurated in Georgia, next to the dam of the Zhinvali hydroelectric plant established somewhat below on the Aragvi river, just as next to the Zages plant sixty years earlier. This one, however, does not portray Lenin. The structure, cast of concrete, has the shape of an ancient Georgian fortress tower, on which warriors stand outside, to protect the women and children clinging close to the wall inside.

Two years later, in 1985, another monument was inaugurated in Georgia, next to the dam of the Zhinvali hydroelectric plant established somewhat below on the Aragvi river, just as next to the Zages plant sixty years earlier. This one, however, does not portray Lenin. The structure, cast of concrete, has the shape of an ancient Georgian fortress tower, on which warriors stand outside, to protect the women and children clinging close to the wall inside.The monument has no inscription, and on the internet there is almost no reference to what it depicts. The Russian sites call it “a war memorial”, and some even “the monument to the workers of the construction of the Zhinvali water reservoir”. Only Google Maps displays next to it the title, only in Georgian, “300 არაგველი”, “the three hundred Aragvians”.

The three hundred Aragvians were three hundred Georgian soldiers from here, the upper valley of the Aragvi river, who during the 1795 Persian invasion, when the promised Russian support was awaited in vain, fought to their deaths against the Persians, like the three hundred Spartans, thereby ensuring the king’s escape. This anonymous monument was erected in their memory here, on the northern military road, clearly indicating who you can rely on when the homeland must be defended, and from which direction you have to defend it. This monument is an unspoken response to the official platitudes of the Friendship Look-out, which, however, has been clearly understood by everyone. Inside, as the traces of soot show, they often light candles, just as in the churches. The reading of the inscription on the circular iron plate around the central iron column is not an easy task even for a Georgian:

სამშობლოს არვის წავართმევთ, ნურც ნურვინ შეგვეცილება, თორემ ისეთ დღეს დავაყრით მტერსაც კი გაეცინება

samshoblos arvis ts'avartmevt, nurtrs nurvin shegvetsileba, torem iset dghes davaq'rit met'ersats ki gaetsineba

“We do not want to rob anyone’s homeland, but nobody can rob our homeland either from us, because we fight so fiercely for it, that even the dead will laugh at it.”

The quote, says Jacopo, while polishing the translation, is taken from the poem of the great patriotic poet Vazha-Pshavela (1861-1915), which was set to melody and sung as an unofficial anthem already in Soviet times.

Mgzavrebi: Vutia vutisofeli (text by Vazha-Pshavela)

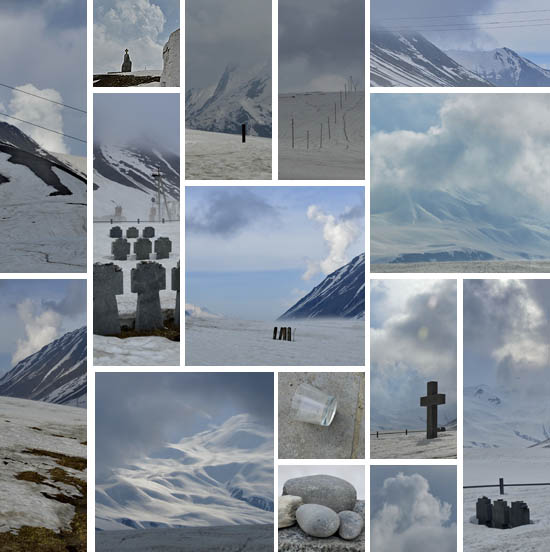

A third monument also stands on the pass, right at the column marking its location, with the cross set on the hilltop, according to tradition, by Queen Tamar. On the map we see a small cemetery here, at the very top of the pass, many, many kilometers from any inhabited place. It arouses our curiosity, and so we stop. Crosses in groups of three. Under the central, solitary cross, an inscription: “Hier ruhen Kriegsgefangene, Opfer des zweiten Weltkrieges.” “Here lie prisoners of war, victims of the Second World War.” After coming back to Berlin, I find in the military cemetery register, that after 1943, German prisoners of war built the road here, across the Holy Cross Pass. Judging from the dimensions of the cemetery, the life of POWs was not everywhere as idyllic as that of Hubert Deneser in Uglich. To this monument of the recruits who senselessly perished after a senseless war, no triumphal or patriotic song belongs. Only the noise of the trucks as they speed along north to the Russian border, the dripping slush, the cawing of the crows that fly over the fields.

A third monument also stands on the pass, right at the column marking its location, with the cross set on the hilltop, according to tradition, by Queen Tamar. On the map we see a small cemetery here, at the very top of the pass, many, many kilometers from any inhabited place. It arouses our curiosity, and so we stop. Crosses in groups of three. Under the central, solitary cross, an inscription: “Hier ruhen Kriegsgefangene, Opfer des zweiten Weltkrieges.” “Here lie prisoners of war, victims of the Second World War.” After coming back to Berlin, I find in the military cemetery register, that after 1943, German prisoners of war built the road here, across the Holy Cross Pass. Judging from the dimensions of the cemetery, the life of POWs was not everywhere as idyllic as that of Hubert Deneser in Uglich. To this monument of the recruits who senselessly perished after a senseless war, no triumphal or patriotic song belongs. Only the noise of the trucks as they speed along north to the Russian border, the dripping slush, the cawing of the crows that fly over the fields.

Holy Cross Pass, cemetery of German prisoners of war. Record by Lloyd Dunn

magyarul

Etiquetas:

brave old world,

Caucasus,

cemetery,

Georgian,

German,

monument,

music,

propaganda,

Russian

The sea in Zahesi

In a short time, the work tool became part of my identity. Its use radically changed my relationship to research. The camera forces you to re-interpret through the lens the meaning of places and people. The flat field and the consequent picture are not the result of a random click. On the contrary, I want to give a conscious visual report on the subject matter of my research. This picture is not merely the view of the space and people existing independently of me, but rather the imprint of an intimate and constant dialogue between us, in which aesthetics and practice merges in an unrepeatable moment.

“What the photograph reproduces to infinity has occurred only once. The photograph mechanically repeats what could never be repeated existentially. The photograph is the absolute particular, the sovereign contingency, the This (this photograph, and not Photography), in short, the Good Luck, the Occasion, the Encounter, the Real.” (R. Barthes, Camera Lucida 1)

The flexibility and practicality of the work tool allows me to constantly reinterpret the environment and society around me. Quickly I discovered that even if I take photos of the same space, my pictures are adjusted not only to research needs of the moment and the intended descriptions, but, as taking photos has already become a part of me, also to my momentary moods and visions. It is also very interesting to put the camera in the hands of my informants, so they shoot with it. These images are “seen-from-inside” views of reality, even more personal representations.

I ran down the stairs of the high-rise building. I wanted to go along the main street that cuts the Zahesi quarter in half, and leading to the Jvari monastery. I was filled with enthusiasm by the device in my hand, the idea that finally I can recount – even to myself – the reality around me.

I ran down the stairs of the high-rise building. I wanted to go along the main street that cuts the Zahesi quarter in half, and leading to the Jvari monastery. I was filled with enthusiasm by the device in my hand, the idea that finally I can recount – even to myself – the reality around me.I got to a hitherto unknown part of the quarter. Some women were engrossed in conversation, the black contours of their clothes sharply outlined in the foreground of the gray blocks of flats. I asked them the way. They stared at the camera, one of them absent-mindedly pointed somewhere. I went that way. Soon I found a small building, half-overgrown by vegetation. On its smooth wall, vigorous figures of dancers and musicians, stiffened only by the immobility of the gray material, not fit for dreams. After the block houses, finally something to test my device appears. It was not easy. I felt I was not yet sensitive enough. After a few clicks, with waning confidence I left the stage.

But the bright sun promised everything good. I cared less about the new toy, and more about finding a suitable object, as if Robert Capa had returned to Tbilisi. Lush vegetation all around, a few dilapidated concrete buildings, nothing else. A couple of little boys came toward me on the street, laughing, either of each other or of me. I did not ask. I had to find my subject myself. After a long walk, the sight of a blue spot pierced through the branches. Perhaps an old fountain, or a playground. I never found out. Fish, waves, seaweed. The tiny tiles of the mosaic were carefully arranged by the worker or artist, commissioned personally by Brezhnev, or maybe only by a local functionary, to bring some liveliness in the housing estate. The sea in Zahesi. Kitano in Zahesi.

Kelaptari: Sacekvao. From the album Georgian Dancing Melodies (2012).

in italiano • auf Deutsch • magyarul

Etiquetas:

anthropology,

brave old world,

Caucasus,

Georgian,

monument,

music,

photo,

ruin aesthetics,

sea

Internationalism

|

|

When traveling from Tbilisi along the Kura towards the Armenian border, after Borjomi a strange Stalin Baroque industrial building appears on the right side. The same oriental version of Stalin Baroque, decorated with high and deep arches, which from the 1930s became dominant in the Caucasus, and which still flourishes in the modern buildings of Yerevan and Baku. Around it, a hamlet of a few houses, its name is Chitakhevi, apparently created to support the power plant.

When traveling from Tbilisi along the Kura towards the Armenian border, after Borjomi a strange Stalin Baroque industrial building appears on the right side. The same oriental version of Stalin Baroque, decorated with high and deep arches, which from the 1930s became dominant in the Caucasus, and which still flourishes in the modern buildings of Yerevan and Baku. Around it, a hamlet of a few houses, its name is Chitakhevi, apparently created to support the power plant.

Although I am in a minibus, I ask the group to wait a few minutes, while I take a picture of the phenomenon. As I approach the building, the guard appears at the gate. “Good morning. What is this facility?” I take over the initiative to prevent his questioning. “The transformer station of the hydroelectric plant.” “When was it built?” “After the war. It started to work in 1949. Where are you from?” “The group from Hungary, I from Germany.” “Well, then it was exactly you who built it.”

The Как воевали плотины project, which documents the history of Soviet hydroelectric plants between 1914 and 1950, devotes a separate article to the large number of Soviet power plants built by German, Japanese, Hungarian and Italian POWs during and immediately after WWII. The article quotes from the memoirs of the German Hubert Deneser, who worked on the construction of the Uglich power plant, also published in Russian. “I worked twenty-two months in Uglich. I had to run up and down a hundred and forty-eight steps with two buckets of water to the cement-mixer. I mastered a lot of construction techniques. When in 1948 I returned from captivity to Germany, I built my house by myself. In the winter, we cut ice from the Volga, in the summer we brought manure out to the fields. There we also met girls, we joked, we laughed.” It must have been an idyllic life.

in italiano • auf Deutsch • magyarul

Electrification

Zahesi quarter. The sound of the name of the Soviet housing estate, established in the north-western edge of Tbilisi to support the hydroelectric power plant suggests ancient Georgian origins. However, the name is neither ancient, nor Georgian. In fact, it is a Russian acronym for Земо-Авчальская ГЭС (гидроэлектростанция), that is,

Zahesi quarter. The sound of the name of the Soviet housing estate, established in the north-western edge of Tbilisi to support the hydroelectric power plant suggests ancient Georgian origins. However, the name is neither ancient, nor Georgian. In fact, it is a Russian acronym for Земо-Авчальская ГЭС (гидроэлектростанция), that is,  “Upper Avchala Hydroelectric Power Plant”, which was built in the 1920s to realize the dream of Lenin, the GOELRO Plan for the electrification of all Soviet Russia.

“Upper Avchala Hydroelectric Power Plant”, which was built in the 1920s to realize the dream of Lenin, the GOELRO Plan for the electrification of all Soviet Russia.

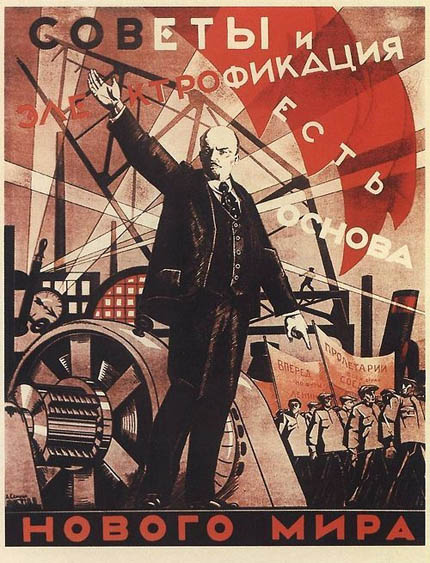

Soviet power plus electrification is communism. The eight flagships of the great plan were designated in 1923, spread all over the country. One of them was allotted to Georgia, partly to industrialize the largest city in the Caucasus, and partly to control the river which often flooded the city. The location of the hydroelectric power plant was sited directly above Tbilisi, where the river Kura enters the city, above the thousand-year-old Avchala village, which only became part of Tbilisi and a Soviet industrial quarter in 1962, and by the present day, a deserted ghost town. True, the power plant reservoir, and according to the old maps, even the dam, belonged to the much more significant Mtskheta. Under this town, the seat of the Georgian Church, the Aragvi river, running down from the northern mountains, discharges into the Kura, which comes from the south. Today, as a result of the damming, they constitute a magnificent frame for the city, even as they cut into some of its lower-lying streets along the river.

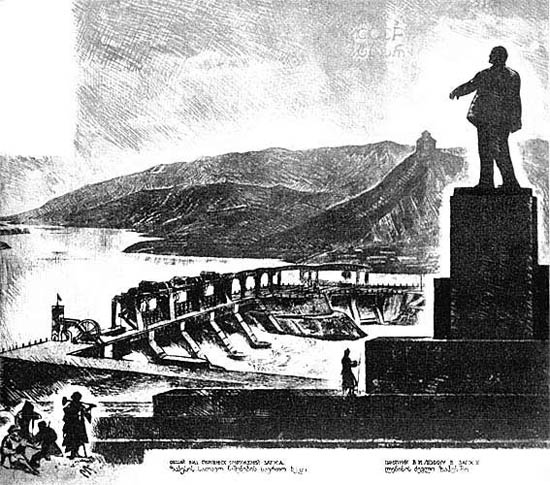

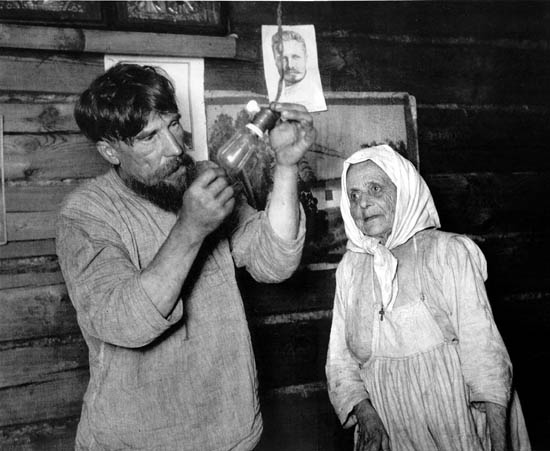

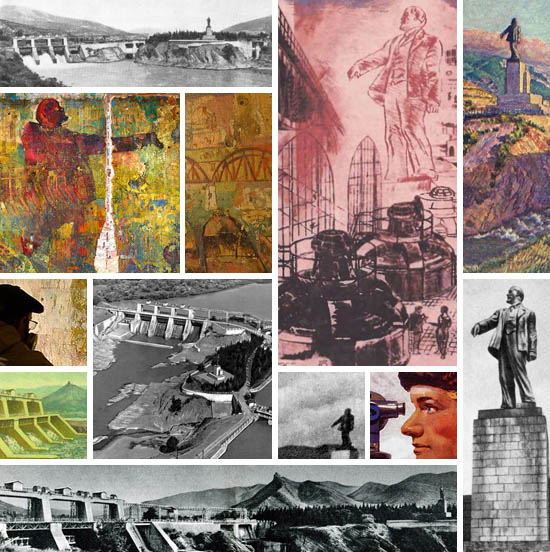

In the period, however, it would have been unimaginable to name a hydroelectric plant after a church center, especially if the former also bore the name of Lenin, as did all of the first eight power stations. It was already disconcerting that, whether they liked it or not, the oldest church in Georgia, the 7th-century Jvari, that is, Holy Cross, towered over the dam. It was surely to visually counterbalance it that, in 1927, after the completion of the power station, they also erected a monumental statue of Lenin next to the dam, one of the first Lenin monuments in the country.

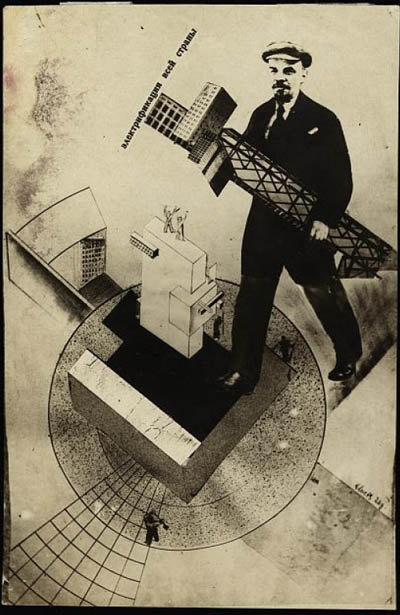

The statue was designed by sculptor Ivan Dmitrievich Shadr (in original name, Ivanov, 1887-1941), whose artistic qualities and revolutionary commitment rested above all suspicion. Before 1917, he studied in Paris, where he was a follower of Bourdel and Rodin, and after 1917 he worked closely with Lenin on the realization of the “monumental propaganda” envisioned by the latter. The Lenin statue planned next to the ZAGES is a major branch of the Lenin iconography, which was solidifying just at that moment, the prototype of the “pointing Lenin”, which would be imitated in thousands of variations across the empire. The type was further popularized by illustrations that propagated the image of the realized hydropower plant across the country, such as the printed graphics of Ignaty Nivinsky, or the monumental fresco by Vasily Maslov, recently discovered in the Bolshevik House in Moscow’s Korolev district.

During the last century, a lot of water flowed down in the Kura. The hydroelectric power plant grew old, and the Georgian state, which has no money for reconstruction, sold it in 2007. The new owner, GeoInCor operates it only intermittently. From the two settlements bearing the name of the plant, the Zahesi housing estate and Avchala industrial quarter, the residents flee. The first one to disappear was Lenin himself, whose statue was removed in 1991. The still vacant pedestal has been charitably covered by the growing trees. If you stop at a certain point of the Mtskheta-Tbilisi road, and look through the small forest, and wade through the knee-high grass to the bank of Kura, you see that after a short interlude, the river and the mountain have taken back their thousand-year-old reign over the landscape.

L. Utesov: Suliko, 1930s

in italiano • auf Deutsch • magyarul

Suscribirse a:

Entradas (Atom)