The Hungarian-language Falanszter blog, a unique online journal publishing thorough articles on the theme of the totalitarian architectural utopias of the 20th century, has just published some excellent research about the little known plans of the Nazi Slovak state (1939-1944) for the building of a monumental university campus in the style of the Italian Fascist architecture in the center of Bratislava, in the place of the centuries-old royal castle. The article, shared by us on the Facebook site of río Wang, has attracted a vivid interest of Slovak readers, who asked for a translation. Here we offer it, in collaboration with the author of the blog Levente Jamrik.

The Hungarian-language Falanszter blog, a unique online journal publishing thorough articles on the theme of the totalitarian architectural utopias of the 20th century, has just published some excellent research about the little known plans of the Nazi Slovak state (1939-1944) for the building of a monumental university campus in the style of the Italian Fascist architecture in the center of Bratislava, in the place of the centuries-old royal castle. The article, shared by us on the Facebook site of río Wang, has attracted a vivid interest of Slovak readers, who asked for a translation. Here we offer it, in collaboration with the author of the blog Levente Jamrik.The Slovak Nazis dreamed about a Bratislava with one million inhabitants, and moved everything in the interest of creating it. A Fascist-style Comenius University would have stood on the place of the Castle.

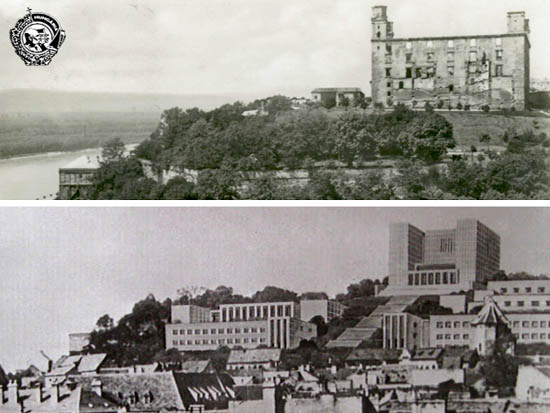

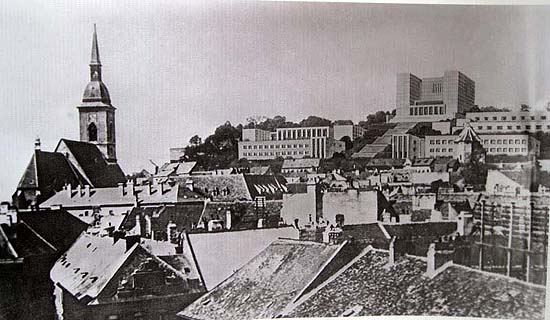

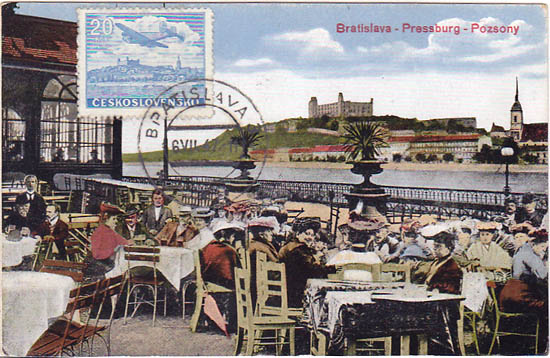

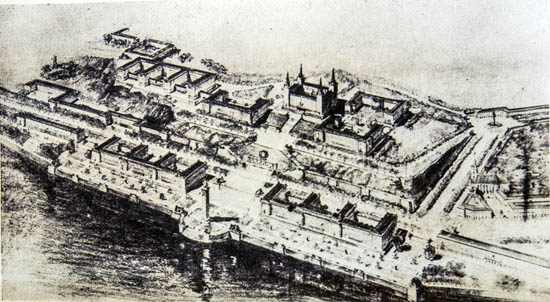

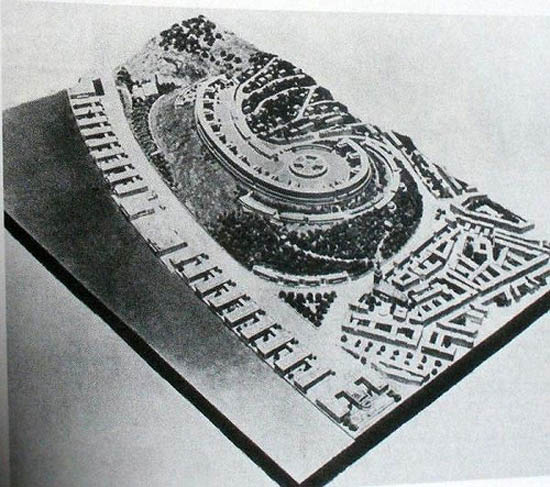

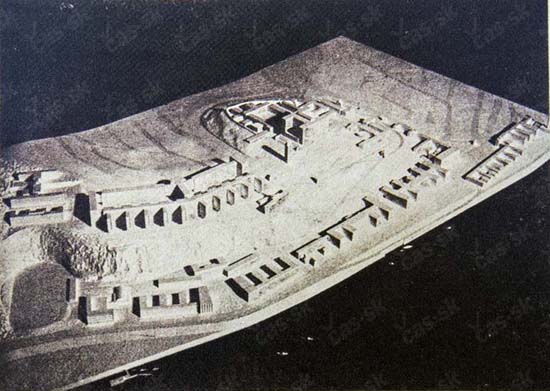

The Castle of Pozsony in 1912, and the Comenius University planned in its place by Ernesto La Padula (1941)

The Castle of Pozsony in 1912, and the Comenius University planned in its place by Ernesto La Padula (1941)

Large or small?

Pozsony – as the city was called before becoming the capital of Slovakia in 1919, when it also changed its former Slovak name Prešporok for the newly coined Bratislava – was not only the capital of historical Hungary between 1526 and 1784, but between 1435 and 1848 it also housed the Hungarian parliament sixteen times. Despite the fact that from 1840 the population of the town at the bank of the Danube grew yearly by 1.75%, according to the census of 1910 “only” 78,223 citizens lived here, which was not outstanding in comparison with other cities of Hungary. As a result, in the second half of the dual Monarchy (1867-1918), Pozsony was more a rather stagnant historical settlement than a dynamically developing regional center. This was also marked by the fact, that the city was “only” the sixth largest (after Budapest, Szeged, Szabadka/Subotica, Debrecen and Zagreb) in the Kingdom of Hungary.

After the change of regime in 1919, the city was allotted a new central role in the life of the Czechoslovakian state. The quick growth of population of the “Eastern capital” of the new state (and after 1939, capital of Nazi Slovakia) can be traced back to three demographic factors: the relatively high natural growth, the planned large-scale settlement of Slovak, Czech and Moravian population into the city, and the high number of soldiers of the Czechoslovak army stationed here. As a result, the census of 1919 registered 83,200 inhabitants, the first Czechoslovak census of 1921 93,189 inhabitants, and the 1930 census already 123,844 inhabitants in Bratislava, so, that in the 12 years following the change of regime, 26% of the population (12,815 persons) either fled to Hungary, or denied their former nationality and declared themselves “Czechoslovak”. Thus the population growth meant actually 58,436 new residents in Bratislava, or people changing nationality, before 1930.

Ethnic structure

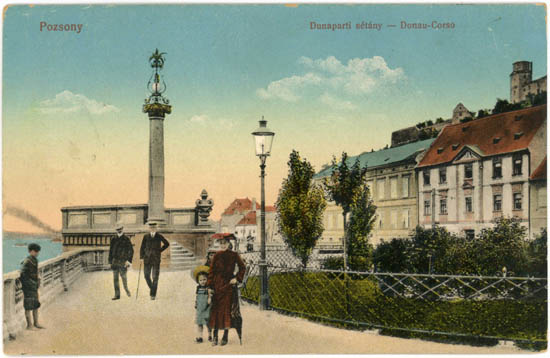

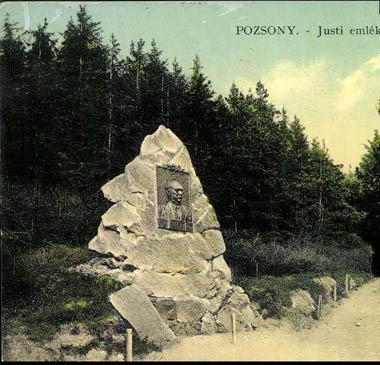

The ban on the Hungarian, German and Jewish languages and the removal of the public inscriptions in these languages, ordered by the Slovak plenipotentiary of the Prague government, Vavro Šrobár, the suppression and closing down of the cultural and scientific institutions of these people, the mass hostage taking, or the fusillade of 12 February 1919 resulting in nine casualties and twenty-eight serious injuries, all aimed at a radical change in the ethnic structure of Bratislava. Simultaneously with the intimidation, they also started to liquidate “the urban and ecclesiastical hallmarks referring to Hungarian and Hapbsburg domination, Hungarian, German and Jewish ethnicity, and the cult of the Virgin Mary”. Thus, the Czech legionaries already in 1918 and 1919 destroyed or irreparably damaged the equestrian statue of Maria Theresa, the Iron Soldier, the bust of city archivist János Batka, the full-length figures of St. Zita, St. Elisabeth and St. John, as well as the reliefs depicting Franz Joseph and Mayor Henrik Justi. In this period, there were destroyed dozens of painted glass windows by Miksa Róth, coats of arms, almost thirty memorial columns (e.g. the Esterházy lighttower) and several plaques, including those in honor of the poet Sándor Petőfi, the novelist Mór Jókai, and the martyrs of the 1848 war of independence Pál Rázga and György Petőcz.

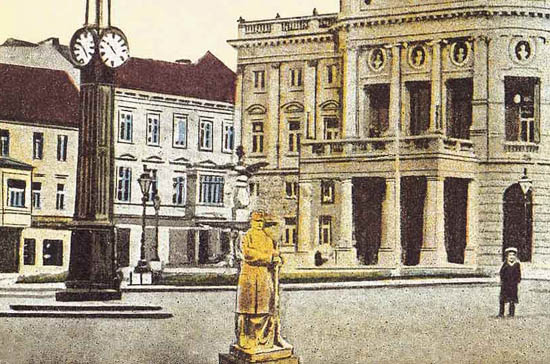

Dr. Viktor Duschek, the first Czechoslovak mayor of the city, in 1921 ordered only removals of some further statues, rather than their destruction. At this time they removed from the city the statue of Sándor Petőfi (Béla Radnai), the relief representing the praying Queen Elisabeth (Alajos Rigele), the statues of playwrights Mihály Vörösmarty, József Katona, Ferenc Liszt, Goethe and Shakespeare (Theodor Friedl) from the façade of the Municipal Theatre, as well as the Ganymedes fountain standing in front of the theatre (Tilgner Viktor). (Petőfi, the fountain and the statues of the theatre have been restored to their original places.)

It was a serious new ubanistic, logistic and housing challenge that the city, whose population suddenly increased, lacked the character or appearance of a national capital. In fact, in the dual monarchy period (1867-1918), there was an unwritten rule, that only those settlements would receive a quasi-metropolitan image: those that actually functioned as centers of regions with strong industrialization, developed traffic and large population (e.g. Prague, Brno, Lemberg, Triest, Ljubljana, Zagreb, Sarajevo), as opposed to smaller regional centers, such as Czernowitz, Troppau, Split, Innsbruck or Bregenz, whose population was much below that of the former ones.

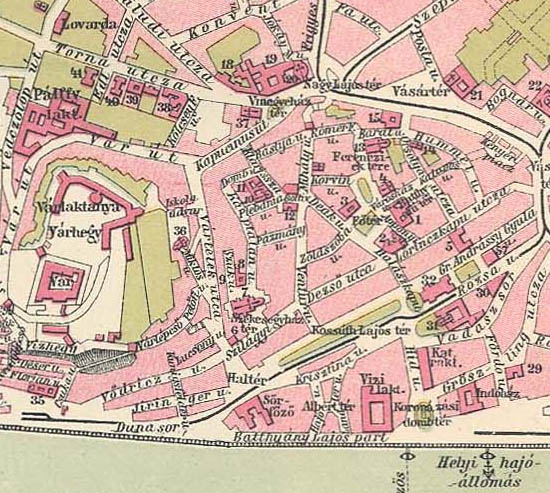

The downtown of Pozsony in 1912 (click for the full map). On the left, the Castle Hill, to the right, the sites of most of the monuments and buildings mentioned above and below.

The downtown of Pozsony in 1912 (click for the full map). On the left, the Castle Hill, to the right, the sites of most of the monuments and buildings mentioned above and below.

Metropolis Bratislava?

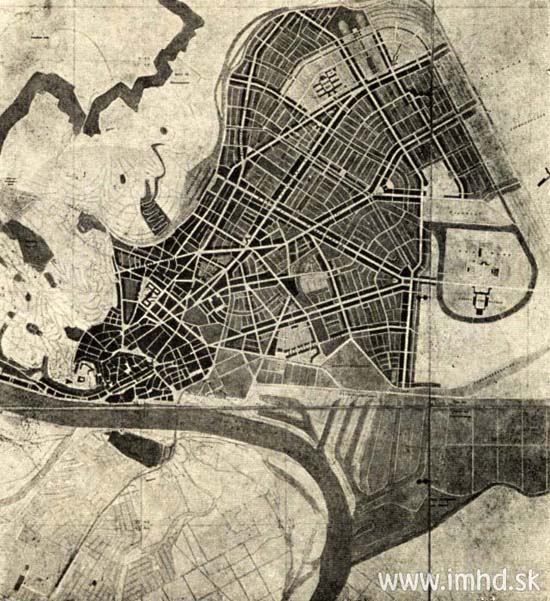

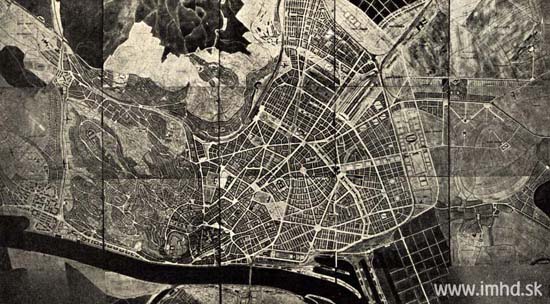

Due to the parsimony of Prague, the first plan for Bratislava, “featuring new avenues and promenades, articulated with more representative and spectacular public buildings” was prepared not at this time, but only in 1929, the last year of the office of Mayor Ľudovít Okánik. The national competition announced that year was won by the trio of Juraj Tvarožek, Alois Dryák and Karel Chlumecký against a field of strong candidates, including Frederick Weinwurm and Ignác Vécsei. However, the concept of the winning design was essentially not new. As the development of Bratislava was inherently limited by the Little Carpathians and the Austrian border to the west, and the Danube and the Hungarian border to the south, the metropolis could extend only towards the north and east, along the Kereszt (today Krížna), Ország (today Radlinský), Récsei (today Račianské) and Nagyszombati (today Trnavská) streets. A modern neighborhood called Nové Mesto, planned around the new railway station and embraced with a central boulevard, was very similar to the New Belgrade which was actually created on the outskirts of the city of Zimony/Zemun in the southern Hungarian region allotted to Serbia. (This plan was ultimately not implemented after the war, due to the Communist takeover.)

Of course, the architectural, urbanistic life had not come to a stop in Bratislava the decade since the change of regime, for already in 1921, there appeared the first buildings of the Czech and later Slovak architects working in the style of Functionalism and “Rondokubism” declared as the “Czechoslovak national style”, which are still officially considered the icons of the city. In the 1920s they inaugurated the YMCA movie theater in Sánc (today Šancová) street (Alois Balan – 1921), the JESPER condominium in Preyss Kristóf (today Heydukova) street (Klement Šilinger – 1923), as well as the high-standard five-storey apartment house in Kempelen Farkas (today Klemensova) street (Jindřich Merganc – 1924). In this period the relatively large housing estate for Czech legionaries was completed along Récsei (today Račianska) street (Dušan Jurkovič – 1924); the five villas intended for politicians in Csalogányvölgyi (today Slávičie) street (Dušan Jurkovič – 1924); the Tátra Bank in Vásár (today SNP) square (Milan Michal Harminc – 1925) and the Slovak National Museum in the Justi promenade (today Vajanského nábrežie) (Milan Michal Harminc – 1928).

The development of “Metropolis Bratislava” continued in the 1930s. In that decade they merged and expanded the Savoy, Palugyay and Carlton hotels in Séta, later Kossuth Lajos (today Hviezdoslavovo) square (Milan Michal Harminc – 1930); they inaugurated the Baťa palace in Nagy Lajos (today Hurbanovo) square (Vladimír Karfík – 1931) and the Lutheran church in Honvéd (today Legionárska) street (Milan Michal Harminc – 1932). The series was continued with high-rise buildings, like the Schön house in Magyar, later Széplak (today Obchodná) street (Ignác Vécsei – 1934), the Royko Passage (Ernst Steiner – 1932) the Manderla house in Vásár (today SNP) square (Christian Ludwig, Emerich Spitzer, Augustín Danielis – 1935) and the Justice palace in Kertész (today Záhradnícka) street (Alexander Skutecký – 1937).

However, the state apparatus of the clerical-fascist First Slovak Republic, declared in 1939, started on an even larger scale town plan, which is well indicated by the fact, that on the order of President Jozef Tiso only such buildings were allowed to be erected in the city, as were worthy of the spirit of the works of Albert Speer in Berlin and Marcello Piacentini in Rome. In these years there was built the already “Nazi-lined” National Bank in Baross Gábor (today Štúrová) street (Emil Belluš – 1939), the Union Bank headquarters in Grössling (today Grösslingová) street (Ernst Steiner – 1944), the office house of the Carpathian German and the Zipser German Parties in Marhavásár (today Odborárskom) square (since then pulled down), and the new working class neighborhood next to the Nobel Dynamite Factory (Julius Ernst Sporzon – 1942). This concept was also followed by a government district planned for the Esterházy (today Námestie) square and its neighborhood, whose foundations were laid after the election of President Tiso. After the announcement of the winners of the 1943 international competition (1. Josef Gočár, 2. Siegfried Theiss and Hans Jaksch, 3. Ernesto La Padula and Alberto Libera), and before the arrival of the Red Army, they only erected the building of the Ministry of Public Affairs on the corner of the street.

Pull down the Castle of Bratislava!

The largest urbanistic dream of Nazi Slovakia, conceived in 1941, was to build a vast university campus extending over the entire Castle Hill of Bratislava. Already in 1465, King Matthias planned to build an “Academia Istropolitana” in Pozsony, but the first actual university was opened under Emperor Joseph II in 1784. In 1912 it took the name of Queen Elizabeth. Although after the 1920 Peace Treaty the campus and the professors moved to Pécs in southern Hungary, it was already felt by the newly declared Slovak state that the university buildings remaining in Bratislava were too few.

From a Slovak point of view, the demolition of the Castle and the complete building over of Castle Hill was a perfect idea and site, because this iconic landmark of the city had been a ruin for exactly 130 years. Until today it is not clear, when on 28 May 1811 a fire started in the winter riding school of the fortress, why the whole castle and other 82 houses burned down. The partial restoration, especially the reconstruction of the Crown Tower and the Sigismund Gate, were already proposed by city archivist János Batka, as well as Mayors Henrik Justi, Mór Gottl and Tivadar Brolly, but after the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867, the residents of Pozsony preferred to look at the symbol of their city as a romantic English Garden in the city center, rather than as a fortress symbolizing military greatness. The Slovak politicians of the early 1940s advocated for the demolition of the Castle not only because of its life-threatening condition, but also in order to clear away the symbol of Hungarian, Hapsburg and feudal oppression.

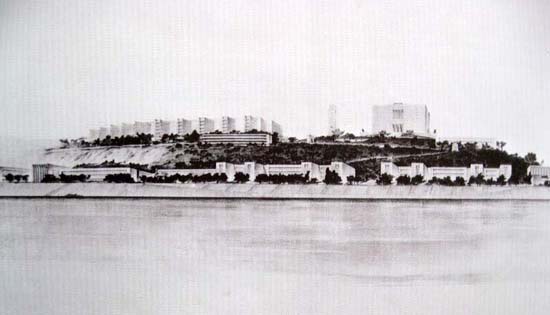

Twenty-four plans were sent to the international architectural competition announced in 1941. Aside from the Slovaks, only Italian and German architects took part in the competition – provided we also consider the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia as a part of the German Reich. With the exception of four plans (that of Lucchini and Pasqui, Roth and Tornack, Dušan Jurkovič and Emil Belluš), all the others depended on the demolition of the palace, in order to comfortably “sprinkle” the educational buildings of Komenský University on Castle Hill, and the colleges and the campus at the foot of Water Hill. The competition was won by the Italian architects Ernesto La Padula and his brother Attilio La Padula, the planners of the university campus and the E.U.R. center of Rome. The second place was awarded to the Germans Franz Kreuzer and Hans Drassler, while the third to the Slovak architect of Hungarian origin Emil Belluš. The landscaping was started in 1942, but soon it was suspended due to the war.

Good Commies, bad Commies

Concerning the later fate of the Castle of Bratislava, it is worth noting, that after WWII, painter Janko Alexy and Czech architect Alfred Piffl managed to convince the Prague and Bratislava Communists, that, contrary to the original plans, the landmark should not be pulled down, but rather reconstructed, so that up to 80% of it would be an “authentic-looking fake”, a replica. While the construction, between 1953 and 1968, brought back a 157-year-old ruin to its original splendor, the Royal Castle of Buda, which survived WWII in much better condition, was completely destroyed by their Hungarian comrades because of “its past recalling the rule of the Hapsburgs and Horthy”.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario