In some previous posts

In some previous posts we have already written about the Austro-Hungarian artillerymen who served in Palestine during WWI. Now, on the occasion of a recently found photo album we will speak about their German comrades in arms, who were present in a much larger proportion at the Palestinian front. At a request by their Turkish allies with the aim of conquering the Suez Canal, in the spring of 1916, a large number of

German units arrived in Palestine, including an air squad, several artillery batteries, a machine gun and mortars company, a radio and anti-aircraft platoon, two field hospitals and several motorized units. In one of the latter, the Kraftwagen-Park 505 – briefly, KP 505 – served the German soldier, whose photo album we recently found on

a web site.

The journey from Constantinople to the Sinai front – to Gaza to be precise, where the German troops came under the command of the Turkish army – took two weeks. The train trip had to be interrupted several times, because the tunnels through the Taurus and Amanus mountains were not yet ready. In an irony of fate, these will be given over to traffic only at the same time of the armistice in late October 1918… The first transit and trans-shipment point was Bozanti (today Pozantı) at the northern foothills of the Taurus, where the troops arrived after a three-day train ride from Constantinople. The ammunition, packages and equipment, as well as the guns of the artillery units, were put on trucks, and the crew crossed on foot the 1,500 meter high passes of the Taurus.

A few days later, now at the southern slopes of the Taurus, they once again boarded the train, and then at the Amanus a new trans-shipment and a new march through the mountain followed. The rest of the road in Syria province – in the territory of today’s Syria, Lebanon and Palestine/Israel – was covered by two other trains.

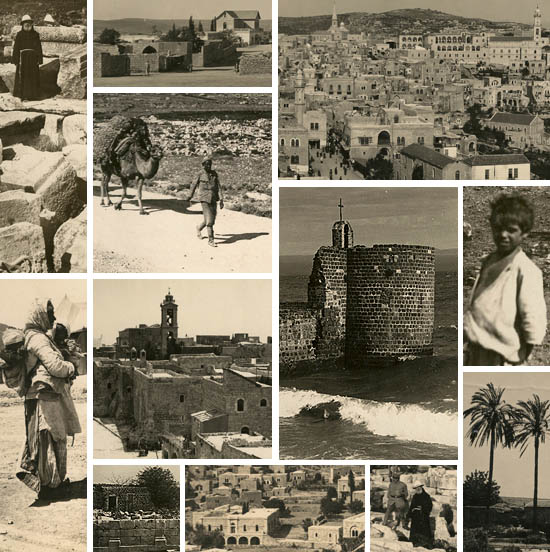

The Middle Eastern scenery and the exotic “natives” certainly had a strong impression on the newly arrived European soldiers. It is no wonder that nearly half of the album’s forty pictures are made up by vistas of the Holy Land, as well as by genre photos representing “Oriental types”, beduins and camel caravans.

In some pictures, the owner of the album failed to correctly identify the captured spectacle. The caption of the following photo is only half true. The well is in Jaffa indeed, but it is not called Jacob’s Well, but rather that of Abu Nabbut –

Sabil Abu Nabbut –, or Tabitha’s Well. The mistake is all the more strange, because – as you will see below – in 1917 the German motorized unit celebrated New Year’s Eve precisely in Nablus, where Jacob’s famous well is still visited.

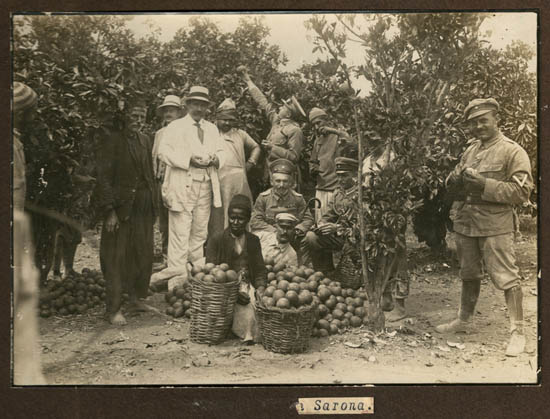

A peaceful moment among civilian compatriots. Sarona was an agricultural colony of the German Templars – a Lutheran millenarian sect – near Jaffa, where they mainly produced oranges and grapes, and operated a winery. The peaceful times were ended by the advance of the British. In July 1918 all the Templars, as citizens of an enemy country, were interned in Egypt. The residents of Sarona were only allowed to return in 1920 to the settlement, which in the meantime had been completely devastated and looted.

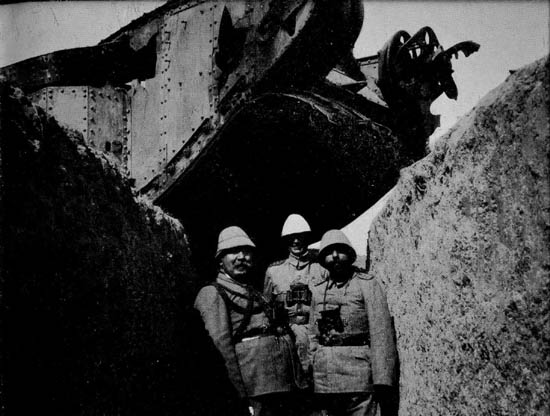

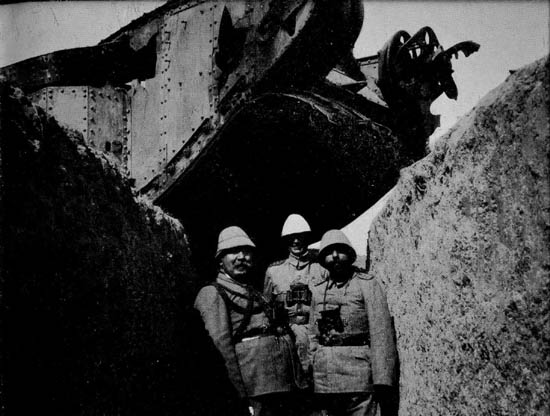

But let us still stay in Gaza. Among the military-themed photos taken here, the first is an old friend: the British tank knocked out by the Austro-Hungarian howitzer battery on 19 April 1917, in the second battle of Gaza. Its photo was already shown in

an earlier post. The complete seven-person crew of the tank, christened the HMLS (His Majesty’s Land Ship)

Nutty, fell into Turkish captivity. Its commander, the thirty-five-year old Lieutenant Frank Carr from Birmingham, was seriously burned while trying to escape the tank, so that shortly after falling into captivity he died in the Turkish field hospital at Tel el Sheria. After the victorious battle even the three Pashas of the Staff – Izzet, Kress von Kressenstein and Djemal – stood proudly posing in front of the shot up tank.

Source: F. Kress von Kressenstein: Mit den Türken zum Suezkanal, 1938

Source: F. Kress von Kressenstein: Mit den Türken zum Suezkanal, 1938

Enver Pasha, the Turkish Minister of War visiting the Turkish and German forces at their headquarters near Beersheba at the beginning of March 1916. In the middle, the bearded Djemal Pasha, commander in chief of the troops in Palestine, and to the left Enver Pasha with raised right hand.

Enver Pasha, the Turkish Minister of War visiting the Turkish and German forces at their headquarters near Beersheba at the beginning of March 1916. In the middle, the bearded Djemal Pasha, commander in chief of the troops in Palestine, and to the left Enver Pasha with raised right hand.

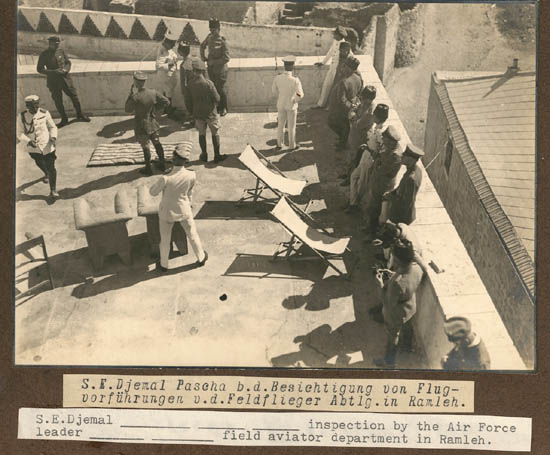

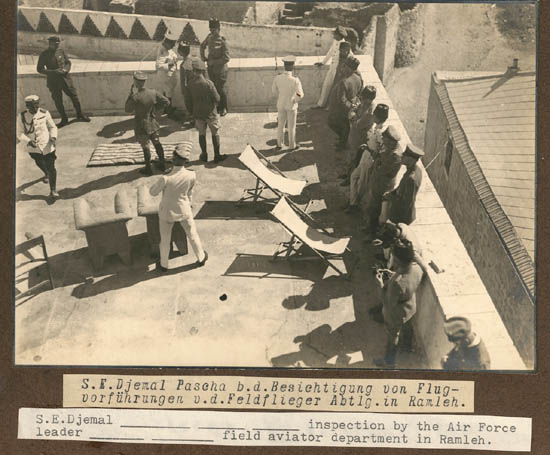

Djemal Pasha in Ramlee, at a German military air show. The pasha is the officer to the upper right of the picture looking in the camera.

Djemal Pasha in Ramlee, at a German military air show. The pasha is the officer to the upper right of the picture looking in the camera.

The commander of Kraftwagen-Park 505, Captain Emil Axster, was captured in several images. In civilian life, Axster was the director of a well-known German bank, and it seems that even in the military service he could not fully put aside the style of a well-dressed bank-clerk. In contrast to his fellow officers buttoned up to their necks in the Prussian style, we always see Axster with turned-down collar, and under that an elegant white shirt and tie, almost ready to jump back into his former civilian role at the sight of an advantageous business opportunity. Axster was welcomed in distinguished circles even in Jerusalem. One of his intimate friends was

Antonio de la Cierva y Lewita,

Count of Ballobar, the Spanish consul in Jerusalem. For the sake of his friend and neighbor in Jerusalem, Axster even arranged the introduction of electricity to the consulate, supplied by the generator of the motorized unit.

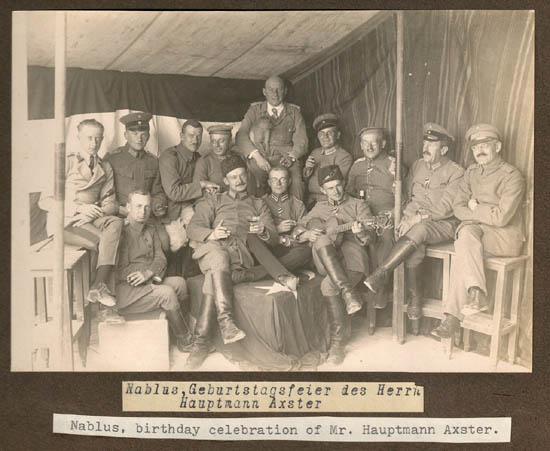

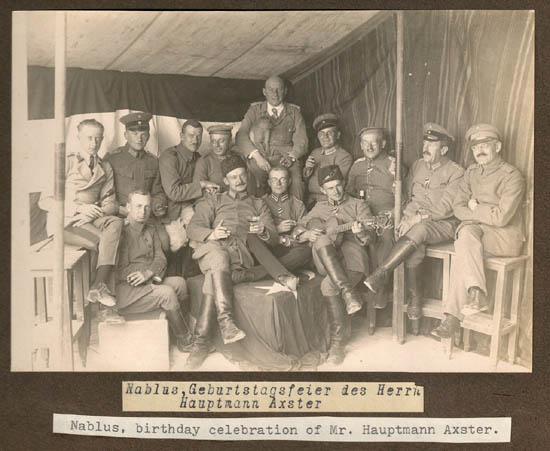

Axster is the third from left in the front row.

Axster is the third from left in the front row.

“Pork dinner” in the casino of the German motorized units in Jerusalem. It would not have been an easy task to find a pig for the dinner in the city, mostly inhabited by Muslims and Jews.

“Pork dinner” in the casino of the German motorized units in Jerusalem. It would not have been an easy task to find a pig for the dinner in the city, mostly inhabited by Muslims and Jews.

Captain Axster in the middle of the back row, with a monkey (!) under his arm, celebrating his birthday. Notice the strategic difference between the positioning of the German and the Turkish imperial flags!

Captain Axster in the middle of the back row, with a monkey (!) under his arm, celebrating his birthday. Notice the strategic difference between the positioning of the German and the Turkish imperial flags!

Of particular interest are the three pictures showing a military funeral in Jerusalem, about which we know many details due to the research of our colleague and friend in Nazareth, Norbert Schwake. In the late night of 16 July 1917, a German military vehicle failed to make a dangerous turn at the northeastern corner of the wall of Jerusalem, slid off the road, and overturned. The driver, Reserve Lieutenant Friedrich Schütze from Kraftwagenkolonne 506, and Lance-Corporal Karl Feldbrügge from Kraftwagen-Park 505,

lost their lives on the spot. One other passenger of the car survived the accident with a skull fracture. The two victims were accompanied to their final resting place, the German and Austro-Hungarian military cemetery on Mount Zion – where their graves still can be seen – in a solemn funeral procession on 17 July at 5 pm. Feldbrügge’s commander, Captain Emil Axster, personally notified the deceased’s family about the tragedy in a detailed letter.

Funeral procession on the way to the military cemetery on Mount Zion. To the right appear the wall of Jerusalem’s old city, in the background the Ottoman clock tower at the Jaffa gate.

Funeral procession on the way to the military cemetery on Mount Zion. To the right appear the wall of Jerusalem’s old city, in the background the Ottoman clock tower at the Jaffa gate.

Another interesting feature is the ecumenical nature of the funeral. Feldbrügge was Catholic, and Schütze Lutheran. This is why the procession is followed both by a Catholic priest and a Protestant minister. Behind the last car carrying the coffin we see Dr. Friedrich Jeremias, the Lutheran pastor of the Jerusalem Erlöserkirche in black robes, and next to him a Catholic army chaplain in military uniform and wide-brimmed hat (Schlapphut).

The funeral was accompanied by the Kraftwagen-Park 505’s own band. It is characteristic that both the German and the Austro-Hungarian units brought with them, as a souvenir of the far away homeland, their own bands to Palestine.

The German troops would not long enjoy the hospitality of the Holy City. In the autumn of 1917, Allenby’s army broke through the Gaza-Beersheba line of defense, and constantly pushed the Turks and their allies north. On 9 December, Jerusalem itself was in British hands.

The British offensive was only stopped for a while by the bitter winter weather. The torrential rains, the overflown vadis, the flooding Jordan, and the deep mud covering the plains after the rains, made any military operations impossible. Thus the Germans retired to Galilea and could celebrate Christmas and New Year in relatively calm conditions. The following New Year’s Eve photo attests that, despite of the not so rosy military situation, the Germans did not fall into melancholy. No doubt that the abundant stocks of Scotch whiskey, French brandy and – in order to drink the enemy’s undoing with their own spirits – of Pfefferminz-liqueur and real Julius Meinl Dominikaner, also played an important part in this.

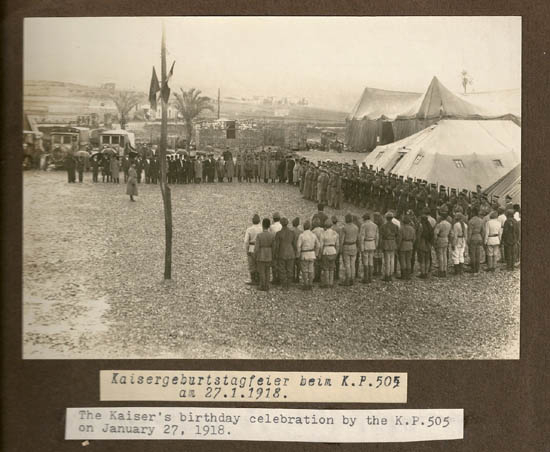

The rainy months at the turn of 1917 and 1918 were captured in several photographs. The rain hopelessly poured down both at the launch of the motor boat

Henriette and –

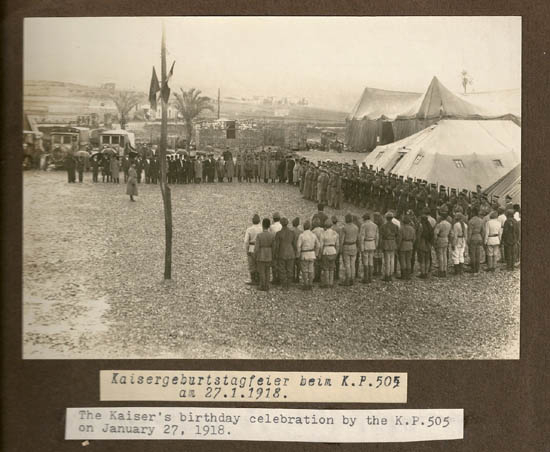

horribile dictu! – on the celebration of the birthday of Emperor William.

The allies celebrating the birthday of Emperor William. To the left, local notabilities, to the right, Turkish soldiers, in the middle, German soldiers, and behind them, partly covered, the brass band of KP 505.

The allies celebrating the birthday of Emperor William. To the left, local notabilities, to the right, Turkish soldiers, in the middle, German soldiers, and behind them, partly covered, the brass band of KP 505.

The following series, which shows a ceremonial procession of the Turkish and German troops and their review by Marshal Falkenhayn, was also taken in Nablus, some time between November 1917 and March 1918.

Erich von Falkenhayn, who on 7 September 1917 became the commander of chief of the Turkish army in Palestine in the rank of Ottoman Field Marshal, moved his headquarters from the advancing British on 14 November 1917 from Jerusalem to Nablus. He could not prevent the further advance of the British troops and the capture of Jerusalem, so on 1 March 1918 he was relieved by the new commander in chief, General

Otto Liman von Sanders.

Falkenhayn – with holster on his side – is the second from left among the officers.

Falkenhayn – with holster on his side – is the second from left among the officers.

Falkenhayn – holding a stick – is the first officer from the right.

Falkenhayn – holding a stick – is the first officer from the right.

In the spring of 1918, the troops of General Liman von Sanders still managed to repel the British attacks in the two Battles of the Jordan, but they could no longer resist the overwhelming offensive of Allenby on 19 September. During the weeks of long, chaotic and bloody retreat, thousands of Turkish and hundreds of German, Austrian and Hungarian soldiers were killed or fell into captivity. We do not know what happened to the unknown original owner of the photo album. It may well be that he and his album were also captured. At least this is suggested by the many incomplete and incorrect English translations glued at a later date under the original German captions.

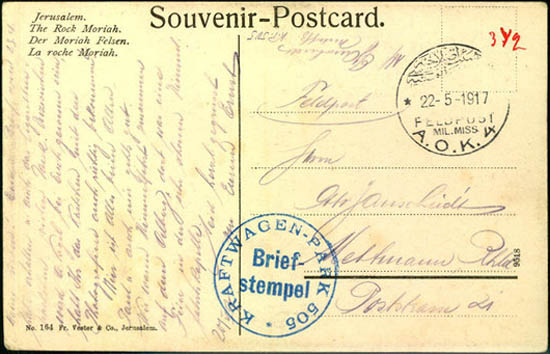

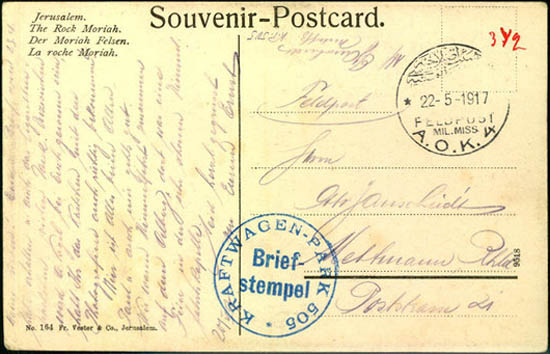

A postcard from Jerusalem with the post stamp of KP 505 (from an auction site)

A postcard from Jerusalem with the post stamp of KP 505 (from an auction site)

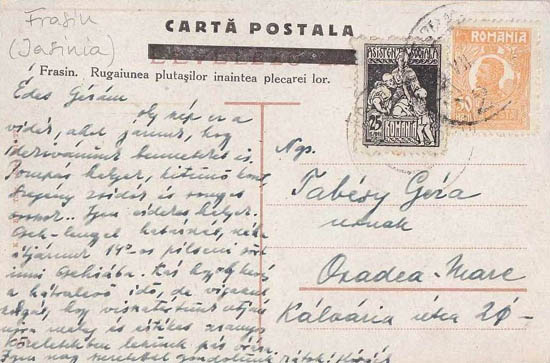

Kőrösmező/Yasinia in today’s Subcarpathia/Zakarpattya, Ukraine

Kőrösmező/Yasinia in today’s Subcarpathia/Zakarpattya, Ukraine As we know, between the two world wars Kőrösmező/Yasinia (at that time Jasiňa) belonged to Czechoslovakia together with the whole Subcarpathia, and it was transferred de facto only in 1944, de jure in 1947 to the Ukraine. However, the above postcard, which we found on an auction site, was sent with a printed Romanian caption and Romanian stamp from Kőrösmező (here called Frasin) to Oradea-Mare. In addition, the sender writes that they “go over” to Czechia to have a beer from Pilsen.

As we know, between the two world wars Kőrösmező/Yasinia (at that time Jasiňa) belonged to Czechoslovakia together with the whole Subcarpathia, and it was transferred de facto only in 1944, de jure in 1947 to the Ukraine. However, the above postcard, which we found on an auction site, was sent with a printed Romanian caption and Romanian stamp from Kőrösmező (here called Frasin) to Oradea-Mare. In addition, the sender writes that they “go over” to Czechia to have a beer from Pilsen.